In occupational health and safety research, the term “psychosocial working conditions” can refer to many different things, each of which deserves to be understood in its own right. Are long work hours harmful to workers’ health? What about lack of training and resources, unclear responsibilities, excessive work demands, unsupportive supervisors and colleagues, to name just a few examples?

But what happens when psychosocial work factors are considered all at once? What happens to workers’ health when negative psychosocial work factors pile on? A new Institute for Work & Health (IWH) study found a clear link. For a segment of the workforce, psychosocial working conditions are poor across the board. And poor conditions overall are associated with a greater likelihood of burnout and stress among workers, the study also found.

“While research on individual psychosocial factors can be useful, this study points to the value of thinking about these working conditions not just in isolation, but all at once,” says IWH Associate Scientist Dr. Faraz Vahid Shahidi, lead author of the study, published in February 2021 in Annals of Work Exposures and Health (https://doi.org/10.1093/annweh/wxaa130) “By doing so, we uncovered four different groups of workers when it comes to the quality of their psychosocial work environment.”

Shahidi says the top segment—with “great” psychosocial working conditions—makes up about 22 per cent of the working population in Canada. That’s the good news. For this first group, representing a rather sizeable proportion of the labour market, the quality of the psychosocial work environment and conditions of work can be quite positive,

he says.

On the flipside, however, is for the fourth group, representing about one in 10 workers, working conditions are overwhelmingly and consistently bad,

Shahidi adds. These workers rated their jobs negatively across all of the work factors included in the study, ranging from emotional work demands and job insecurity to job control and organizational justice.

One notable finding is that these groups had an order to them, with some reporting consistently great working conditions and others reporting consistently bad working conditions. While we sometimes hear about jobs that have mixed exposures – really good in some ways but bad in others – we didn’t find this group of workers in our data,

says Shahidi.

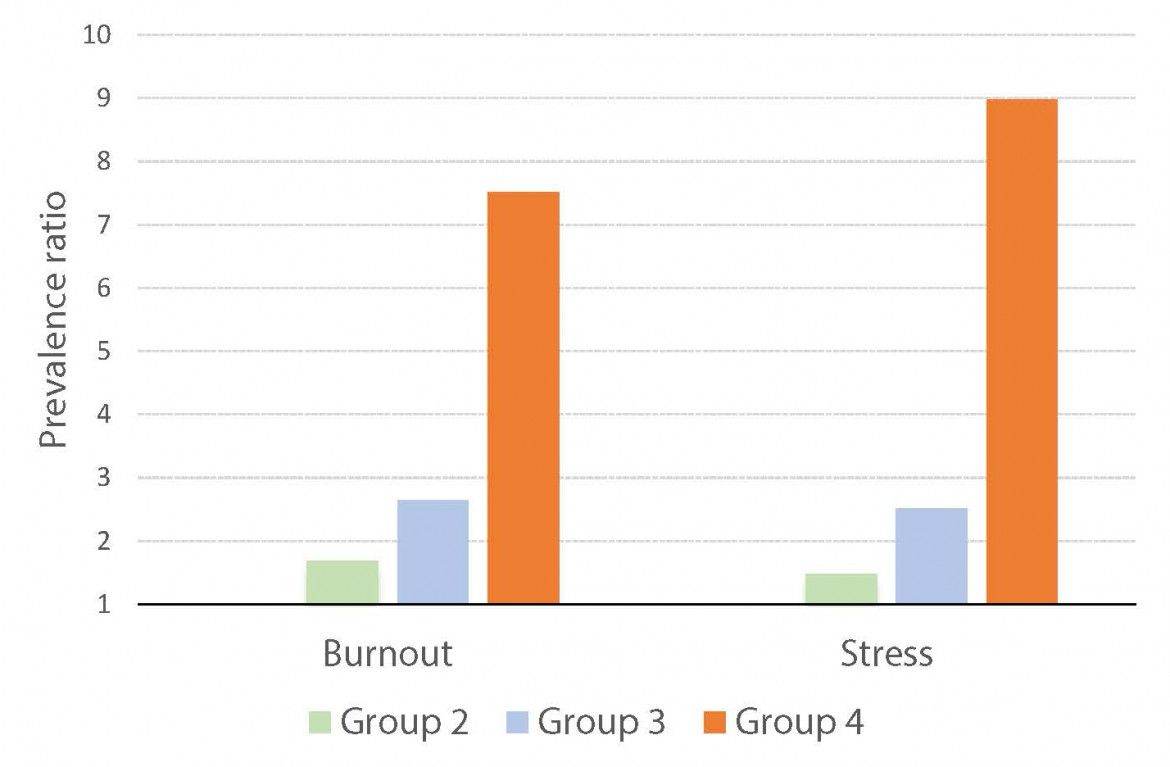

What’s more, Shahidi’s research team saw a rise in the prevalence of mental health symptoms as job conditions worsened. In the first group, burnout and stress were reported by 5.2 and 3.2 per cent of respondents respectively. In the fourth group – those with the worst job conditions – these symptoms were reported by 34.1 and 26.3 per cent respectively.

When other personal and workplace factors were taken into account, workers in the fourth group were 7.5 times more likely to report burnout, compared to their counterparts in the first group. Their likelihood of reporting stress was 9.0 times that of the first group (see sidebar).

In the process of uncovering these various segments of the working population, we’ve shown how mental health outcomes track very tightly with psychosocial job quality,

says Shahidi. While we did not test causal relationships, our findings certainly support the idea that enhancing the psychosocial quality of employment in the Canadian labour market could lead to significant improvements in workers’ mental health.

Uncovering labour market segments

This study is one of several conducted by a team at IWH and the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers (OHCOW). It uses data from OHCOW’s Canadian National Psychosocial Work Environment Survey, a population-based, cross-sectional (or “moment in time”) survey exploring in detail the psychosocial work environment in a large sample of Canadian workers.

The analytical method used in this study, called latent class analysis, allowed the researchers to identify subgroups of workers that have characteristics in common. This method of analyzing data is premised on the idea that membership in such subgroups can explain underlying response patterns picked up in surveys.

Respondents were drawn from an existing panel of 100,000 Canadians maintained by EKOS Research Associates; they were eligible to take part in the survey if they worked in an organization with six or more employees. Survey invitations were sent out in two cycles: once in February and March 2016, and again in February and March 2019. From a total of nearly 13,000 surveys (representing a response rate of 12 per cent), the team ended up with 6,408 respondents who met study criteria and completed key questions.

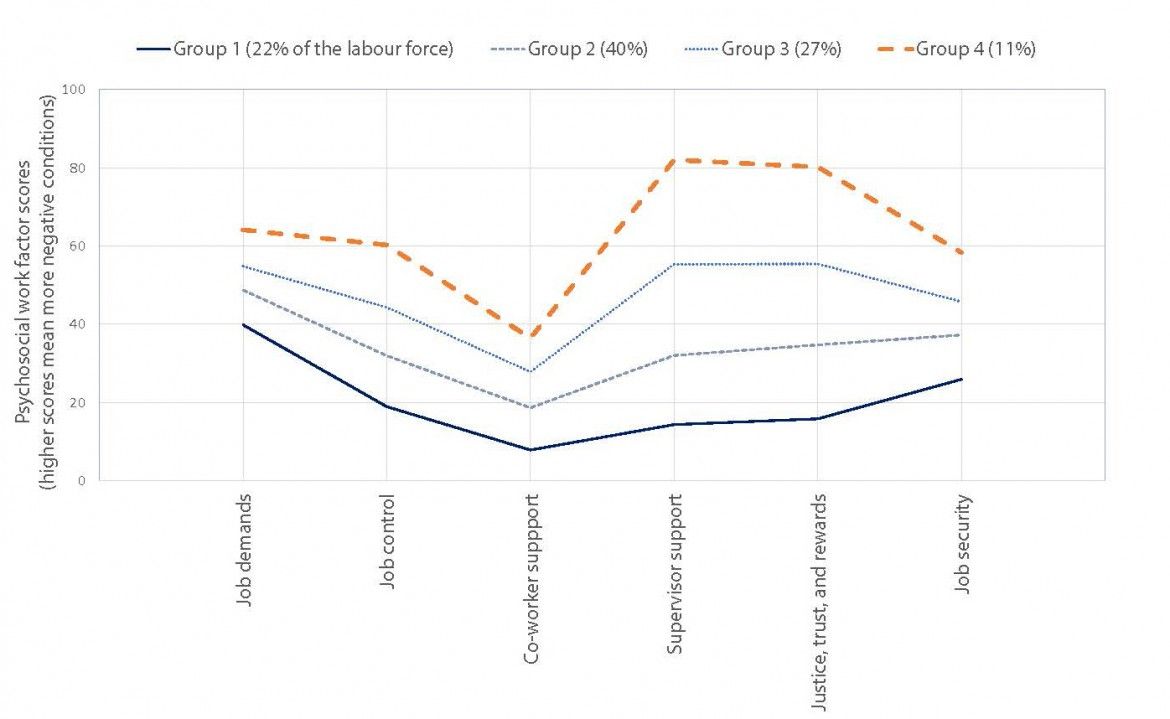

The survey included 36 questions taken from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ), measuring 15 dimensions of the psychosocial work environment. Shahidi and team grouped these dimensions into six psychosocial work factors: 1) job demands; 2) job control and meaning; 3) co-worker support; 4) supervisor support; 5) justice, trust and rewards; and 6) job security. The team then used the survey scores across these six factors to sort the sample of respondents into four different groups or profiles.

Four profiles

Across the four groups, the smallest variations in scores of psychosocial job quality were found in the factors related to job demand and co-worker support. The two factors with the largest spread in scores were supervisor support and justice, trust and rewards. The first group, the 22 per cent of the sample that had the best job conditions, had more older workers and higher proportions of people with more education or in managerial jobs. This group had twice as many people working in professional, scientific and technical services as the fourth group, the one with the worst job conditions. This latter group had more people with rotating or irregular shifts; it also had three times the proportion of workers in transportation and warehousing as the first group.

In one of the study’s notable findings, the team found similar proportions of people in full-time versus part-time or casual contracts in all four groups. Indeed, many of the demographic and socioeconomic factors that are known to predict psychosocial job quality were not strongly related to the psychosocial work environment profiles that emerged from our sample,

says Shahidi. “Although we saw some differences between groups with respect to age, education and industry, in our sample at least, exposure to favourable versus unfavourable psychosocial work environments could not be explained simply in terms of personal and labour market characteristics.”

The study highlights the importance of considering a broader set of psychosocial work factors than the conventional approach of assessing job demands and job control only. The associations we found in this study are stronger than what has been found in previous studies,

says Shahidi. While the work environment is complex and made up of many related dimensions, research tends to neglect the fact that these various aspects of job quality are highly correlated and act in tandem to influence psychological health and safety at work.

Many studies in this field set out to examine the effects of individual stressors—often by statistically controlling for the other stressors that may be present, notes Shahidi. Such study designs certainly have value. However, for that segment of the population for whom working conditions are bad across the board, focusing on a single aspect of work while leaving all the other negative factors intact—that may not get us very far towards improving job quality and mental health outcomes for these workers,

says Shahidi.